Day and night, the roar of trucks hauling stones and sand from quarries across the country to Kigali and other construction zones never ceases. The demand for materials on construction sites is relentless; hammers echo as workers tirelessly mix sand and cement. In many areas, sites known as “Indege” serve as gathering points for laborers, hoping for daily work opportunities. Not all find employment every day, but few employers leave without hiring at least some. As one building rises, another begins. Meanwhile, quarries remain in full swing, with truck drivers receiving constant calls for more stone and sand deliveries.

Philemon, a truck driver in Kamonyi District, has been transporting stones for over a decade. On this particular day, he is at a quarry in Nyabitare Village, Runda Sector, Kamonyi district. True to its name, this village is a hub of rock extraction. On the hills, extractors work shirtless, wielding crowbars and heavy hammers. Workers load trucks in shifts to maintain a steady supply. “Today, I’ll make at least four trips,” Philemon estimates.

But as stones are extracted, another reality unfolds: tons of displaced land are left behind. Descending the hill, one sees scars of past exploitations. Some abandoned quarries have been turned into makeshift homes, while others remain as gaping wounds in the landscape, leading to erosion that threatens forests and farmland below.

Rwanda’s 2023 law on mining and quarrying mandates, in Article 39, that all licensed operators must restore degraded sites, fill pits, replant trees, dismantle installations, and level extraction zones following environmental impact studies. Article 41 also introduces an “environmental deposit,” requiring quarry operators to allocate funds for site rehabilitation post-extraction. But is this money being effectively used? The answer seems to be no. Many quarries remain abandoned once extraction ceases, with no trees replanted or any restoration activities undertaken in most of these sites.

A serious concern

The environmental impact of mining has prompted Rwanda’s Parliament to summon the Rwanda Mines, Petroleum, and Gas Board (RMB) for discussions. Lawmakers note that mining has long ignored environmental consequences, and despite revised regulations, destruction persists.

MP Mukabalisa Germaine acknowledges the environmental deposit requirement as a good initiative but points out its inadequacy. “Some operators provide deposits that fall short of actual rehabilitation costs,” she says. “How do we determine the right amount if the money proves insufficient when restoration is needed?” The deposit’s purpose is to ensure rehabilitation; if the inspection confirms proper restoration, operators get their money back—if not, the deposit is used for necessary repairs. Kamanzi Francis, RMB’s Director General, explains that licensed operators must conduct environmental impact assessments and contribute 10% of their extraction value to FONERWA, a fund meant to offset environmental damage. However, the law also requires that sites be restored to their original state. In practice, some operators evade responsibility, moving to new sites without rehabilitating the old ones. “When asked why they don’t restore, they claim they will return for remaining stones, but they don’t. These abandoned pits, often near residential areas, pose serious risks,” Kamanzi explains.

With Rwanda’s high population density; 591 per km2 , land use is under immense pressure, especially in rural areas where much of the population resides. Given that 81.7% of Rwandans live outside urban centers, some mining and quarrying operations are often located near human settlements, increasing the risks to local communities.

A resident of Ndiza, in Muhanga District, confirms the dangers: “Over time, erosion worsens, and in rain season, these abandoned sites collect stagnant water, leading to mosquito infestations, malaria, and accidents. In some areas, some even become hideouts for criminals.”

A report released by the Rwanda Mines and Gas Board (RMB) in January 2025 exposes the scale of neglect in the mining and quarrying sectors. The analysis reveals that 994 sites, including 439 mining areas (44%) and 555 quarries (56%), have been exploited without proper rehabilitation across various regions of the country over nearly a century. The report further underscores the need for approximately 26 billion Rwandan francs to restore these areas to a sustainable state.

Additionally, 367 sites have been left abandoned, with many having been exploited in the past, particularly during the colonial era. Of these, 318 were worked on in violation of recent laws, 166 older quarries were granted to private operators under permits, and 130 others were exploited more recently by permit holders but remain neglected.

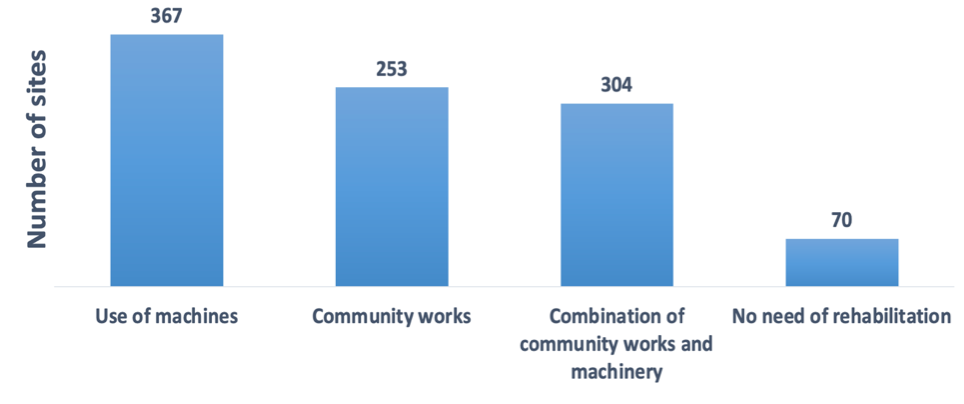

The RMB clarifies that, of the 367 pits, 253 have been rehabilitated through community-led efforts, 304 have undergone combined rehabilitation using both community labor and machinery, while 70 pits did not require restoration. To address the issue, a number of corrective measures have been implemented. Authorities have initiated a site rehabilitation program that involves community work, in partnership with local authorities. In 2024, 53 out of the 253 listed sites were restored, and companies responsible for exploitation have been given six months to rehabilitate abandoned sites. Discussions are ongoing to secure the required funding for restoring these areas, with plans to mobilize a 26 billion franc budget.

Furthermore, RMB says that the authorities are working to strengthen monitoring and enforcement in the mining sector, introducing progressive rehabilitation efforts as soon as exploitation activities end in any area.

A boon for some, graves for others

Mining is a goldmine for some but a graveyard for others. While precious mineral miners often follow safety standards, quarry workers generally do not. Many rely on traditional methods, leading to fatal accidents.

In 2022, in Busogo Sector of Musanze, in the north, a 28-year-old woman died in a sand quarry used for brick-making. The ground was fragile, and as people dug deeper, they left an unstable slope that collapsed. On the same hill, a 60-year-old woman had previously been injured in similar circumstances and, after suffering, died from her wounds.

In other areas where quarrying takes place on hillsides, people living below these areas face significant dangers. “Sometimes, the soil they exploit descends downstream, exceeding the planned limits. As the soil becomes heavier, it exerts more pressure on the land, which can lead to major landslides or collapses during the rainy season,” explained Twiringire Samson, an environmental specialist.

What is particularly concerning is the mining of precious minerals, especially when it is done illegally. In remote areas of Rwanda, illegal mining continues to cause havoc, with frequent human tragedies. Districts such as Rulindo, Huye, Ngororero, and Rutsiro have become symbols of the grim reality of informal mining. These regions, rich in minerals, attract desperate miners by night seeking fortune, only to end up sacrificing their lives in precarious working conditions.

In February 2025, Hagenimana George, a 26-year-old man from Rubavu District, lost his life after being buried in an abandoned mine in Rutsiro. As part of a group of illegal miners known as “Abajongo,” he was attempting to extract a mineral called “igishonyi cya Berire” when a landslide trapped him under the rubble. His companions survived, but he was found dead the following day. According to the police, the accident site had previously been exploited by the Lepierre company before being closed for non-compliance with regulations. A month earlier, in January 2025, another tragedy occurred in the Rulindo District, where 20-year-old Niyonizera Savelin died while attempting to illegally extract gold with two teenagers. His mother, devastated, condemned the exploitation of young people in such dangerous activities: “When we were called to announce Savelin’s death, we were all in shock. We are struggling to accept this tragedy. Those who employ these children should be prosecuted because they expose us to such losses.” According to his mother, her son was working for someone else.

The previous year, several similar accidents mourned the country. In November 2024, a landslide in Rulindo killed eight people. In August, nine miners died in Rutsiro, two of them killed instantly and seven others suffocated by toxic gases in a poorly ventilated mine. In September, six miners died in a collapse in Huye, and their bodies were never recovered. In July, another accident in Rulindo killed three people. Finally, in March 2024, five workers died in an unregulated mine in Ngororero.

Illegal mining is supported by an illicit market driven by buyers seeking cheap minerals. These buyers, operating outside of known legal channels, purchase minerals extracted under such dangerous conditions and arrange to sell them at trade counters. According to an agent from the Rwanda Investigation Bureau, “Legal buyer networks are directly responsible for this situation. They purchase minerals extracted under dangerous conditions, which forces miners to take huge risks.”

The Law No. 072/2024 of 26/06/2024 on Mining and Quarry Operations stipulates that anyone who sells minerals extracted illegally commits a crime. Upon conviction, they may face a prison sentence of more than five years but no more than ten years, along with a fine ranging from at least 60 million Rwandan francs, but not exceeding 120 million Rwandan francs, or one of these penalties.

Rwandan authorities are working to improve mine regulations and safety, but poverty and lack of alternatives force many workers to take dangerous risks for minerals. Despite efforts to close illegal mines and strengthen inspections, these measures haven’t ended the cycle of tragedies.

Complicity with local authorities

Illegal mining and quarrying cannot exist without the direct or indirect involvement of local authorities. In some remote areas of the Southern Province, particularly in Huye, local officials face persistent accusations of complicity in illegal mining, an activity that causes both environmental damage and human tragedies.Residents, often witnesses to these practices, claim that these activities are only possible due to the protection of certain local leaders. Étienne Muramira, a resident of the Rwaniro sector in Huye, questions, “How can we claim that authorities are not involved when these activities take place in the cells and villages where they reside?”

The situation has become a vicious cycle, where the fight against illegal mining is hindered by entrenched local complicity. In the West, the executive council of Rutsiro District was dismissed in 2023, accused of no longer serving the public but rather defending their own interests. Reliable sources indicate that council members were involved in the illegal trade of sand and minerals, which led to internal conflicts. This chaos eventually resulted in the removal of the provincial governor, who was also suspected of being part of this lucrative network. Rwandan police spokesperson ACP Boniface Rutikanga has reliable information: “Sometimes, we organize operations to apprehend offenders. But when we arrive, the suspects have already disappeared. This suggests they were warned in advance. Those providing this information are likely profiting from it.” In fact, when authorities are complicit in illegal mining, monitoring and regulating mining activities becomes nearly impossible. This involvement creates a cycle of impunity, making it difficult for law enforcement to effectively address the issue and hold offenders accountable, allowing illegal mining to continue unchecked.

In 2023, mineral exports brought over 1.1 billion dollars to Rwanda, marking a 43% increase compared to 772 million dollars in 2022. Gold, cassiterite, coltan, and wolfram were the main revenue sources. However, it is difficult to assess revenue from stone and sand quarries, as sales are made informally between individuals, with prices varying by region: a truckload of stones costs between 80,000 and 120,000 Rwandan francs (around 57 to 85 USD), while a large truck of sand can range from 400,000 to 700,000 Rwandan francs (around 284 to 497 USD), with areas lacking resources being the most expensive.

The pursuit of profit and human greed, coupled with the growing demand for construction materials, continue to worsen the situation. The increased demand for stones, sand, and other materials driven by a booming real estate sector, along with the global demand for gold, coltan, cassiterite, etc., places additional pressure on already fragile natural resources.

In response to this alarming situation, voices are rising to denounce the dangers of this unchecked exploitation. “If we do not stop this uncontrolled destruction of ecosystems, we are heading towards an ecological and human disaster. The soil is impoverished, biodiversity is disappearing, and local communities are bearing the brunt,” warns Jean-Baptiste Ndayisaba, an environmentalist and advocate for natural resource preservation. He calls for urgent action to raise awareness, impose strict regulations, and penalize offenders to prevent this crisis from becoming irreversible.

Fulgence Niyonagize